February 2nd, 2026

In the realm of literacy education, few models have provided as much clarity and insight as Scarborough’s Reading Rope. Created by Dr. Hollis Scarborough in 2001, this visual metaphor elegantly breaks down the complex, intertwined skills involved in becoming a proficient reader. Whether you’re a teacher, literacy coach, or parent looking to support young readers, understanding this model is key to fostering effective instruction and targeted intervention.

In this blog, we’ll explore what Scarborough’s Reading Rope is, how it works, and how educators can use it as a framework for teaching reading. By the end, you’ll have Scarborough’s Reading Rope explained in detail—bringing you closer to mastering the art and science of reading instruction.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Scarborough’s Rope Model of Reading

- The Origin of Scarborough’s Reading Rope

- Breaking Down the Strands: Language Comprehension

- Breaking Down the Strands: Word Recognition

- How the Strands Work Together

- Why Use the Reading Rope for Teaching Reading?

- Scarborough’s Rope Model vs. Other Reading Theories

- Practical Applications in the Classroom

- Scarborough’s Reading Rope Explained for Parents

1. Introduction to Scarborough’s Rope Model of Reading

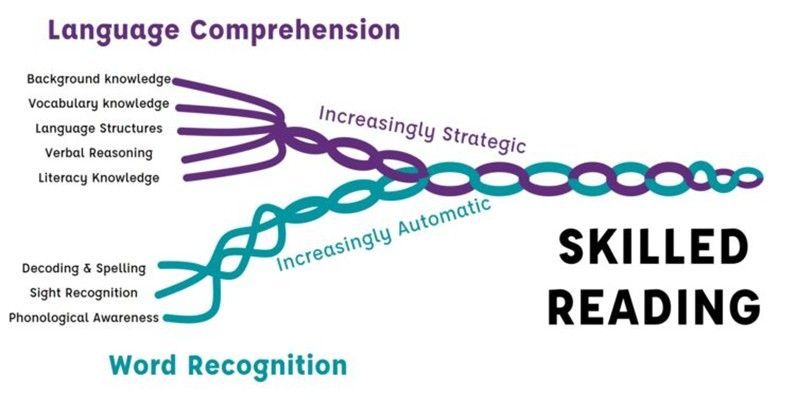

Scarborough’s Reading Rope model is a powerful framework that helps educators visualize and address the many intertwined skills necessary for reading success. The model represents skilled reading as a rope woven from two major strands:

- Language Comprehension

- Word Recognition

Each of these strands is further composed of smaller, interconnected components that must develop together. The stronger and more automatic these skills become, the more fluent and skilled a reader becomes.

Why Is the Reading Rope Important?

Understanding the reading rope is critical for:

- Diagnosing reading difficulties

- Planning effective instruction

- Aligning with the Science of Reading

- Supporting struggling readers with evidence-based interventions

2. The Origin of Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a leading reading researcher and psychologist, introduced the reading rope model in 2001. Her goal was to synthesize decades of literacy research into a format that educators could easily understand and use. She used the metaphor of a rope to represent how multiple reading skills intertwine and reinforce one another over time.

Her model gained traction as reading researchers and educators sought to bridge the gap between scientific research and classroom practice. Today, Scarborough’s rope model of reading is widely cited and used as a central element of literacy instruction programs aligned with the Science of Reading.

3. Breaking Down the Strands: Language Comprehension

The language comprehension strand includes the skills readers use to understand spoken and written language. It is crucial for making meaning from text and involves higher-order cognitive processes.

The five key components in this strand are:

a. Background Knowledge

Includes understanding of the world, facts, concepts, and vocabulary acquired through experience or instruction.

b. Vocabulary

Knowledge of word meanings and the ability to use and understand a wide range of words.

c. Language Structures

Grammar, sentence structure, and understanding how language is used in context.

d. Verbal Reasoning

The ability to reason through spoken or written language, including inferencing, understanding sarcasm, idioms, or figurative language.

e. Literacy Knowledge

Understanding of print concepts, genres, and other conventions of written language.

As these components become more automatic, they contribute to a reader’s overall comprehension ability.

4. Breaking Down the Strands: Word Recognition

The word recognition strand deals with the decoding side of reading—the ability to recognize and process printed words efficiently and automatically.

It comprises three primary components:

a. Phonological Awareness

The ability to identify and manipulate the sounds of spoken language (e.g., rhyming, segmenting, blending).

b. Decoding (and Spelling-Sound Correspondence)

Recognizing the relationship between letters and sounds to read unfamiliar words.

c. Sight Recognition of Familiar Words

The instant recognition of words without needing to decode them letter-by-letter.

The goal of this strand is reading fluency, which frees up cognitive resources for comprehension.

5. How the Strands Work Together

The two main strands—language comprehension and word recognition—start off separately but gradually become more integrated. As students develop fluency in word recognition and deepen their language comprehension, they begin to read effortlessly and understand more complex texts.

This gradual intertwining of skills explains why reading is not a single ability but a synergistic process involving both decoding and understanding. If either strand is weak, reading proficiency suffers.

6. Why Use the Reading Rope for Teaching Reading?

Using Scarborough’s Reading Rope for teaching reading allows educators to pinpoint exactly where a student may need support. It provides a framework to:

- Identify specific reading difficulties

- Align instruction with reading development stages

- Support differentiated instruction

- Scaffold students toward mastery in both decoding and comprehension

Addressing Reading Gaps

For example, a student struggling with fluency may need more work on decoding and sight word recognition, while another student who decodes well but doesn’t understand what they read might need intervention in vocabulary and background knowledge.

7. Scarborough’s Rope Model vs. Other Reading Theories

There are other models of reading development, such as:

- The Simple View of Reading (Reading = Decoding × Comprehension)

- Chall’s Stages of Reading Development

- The Five Pillars of Reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension)

While these models have their value, Scarborough’s rope model of reading offers a more granular and integrated view of what reading proficiency entails. It not only supports the Simple View of Reading but also expands it, illustrating how multiple subskills work together dynamically.

8. Practical Applications in the Classroom

Early Elementary (K–2)

Focus heavily on the word recognition strand:

- Systematic phonics instruction

- Phonological awareness activities

- Repeated reading for fluency

- Introducing vocabulary through read-alouds

Upper Elementary (3–5)

Shift gradually toward language comprehension:

- Vocabulary development through morphology

- Complex sentence structure and grammar lessons

- Text structure awareness and comprehension strategies

Middle and High School

By now, word recognition should be automatic. The focus moves to:

- Deepening verbal reasoning

- Analyzing complex texts

- Developing academic language

Intervention Programs

Programs using the reading rope for teaching reading can tailor interventions to specific strands—whether it’s decoding or comprehension—based on diagnostic assessments.

9. Scarborough’s Reading Rope Explained for Parents

Parents often wonder why their child struggles with reading despite seeming intelligent. The reading rope explained simply shows that reading isn’t a natural skill; it requires mastering multiple interrelated abilities.

How Parents Can Help

- Read aloud to build background knowledge and vocabulary

- Play phonemic awareness games

- Use decodable books to reinforce phonics

- Ask comprehension questions during and after reading

- Expose children to a variety of text types and genres

The reading rope model reassures parents that struggles in reading can often be traced to one or more specific, addressable strands.

Case Study: Applying the Rope in Real Classrooms

To illustrate the power of Scarborough’s Reading Rope, let’s look at a real-world scenario in a second-grade classroom. Mrs. Thompson, an experienced elementary school teacher, noticed that several of her students were falling behind in reading comprehension despite performing well during phonics drills.

Using the rope model, she reassessed her instruction by examining each strand. She discovered that while her students excelled in phonological awareness and decoding (word recognition), they struggled with verbal reasoning and background knowledge (language comprehension). As a result, she adjusted her teaching plan to include more content-based read-alouds, discussions to build knowledge, and vocabulary-rich activities that exposed students to diverse language structures.

After a few months of targeted instruction based on the rope strands, she observed measurable gains in reading comprehension and engagement. This case demonstrates how Scarborough’s model allows educators to identify the exact areas that need reinforcement, leading to more effective and individualized teaching.

Integrating the Rope into Curriculum Planning

One of the most valuable aspects of Scarborough’s Reading Rope is its ability to guide curriculum planning across grade levels. Instead of focusing solely on broad reading outcomes, the rope encourages teachers to address each sub-skill explicitly and systematically.

For example:

- In Kindergarten, the focus might be on building phonemic awareness, letter-sound correspondence, and exposure to rich oral language.

- In First Grade, lessons can emphasize decoding strategies, sight word fluency, and oral comprehension through structured dialogue and guided reading.

- By Third Grade, instruction should bridge the two strands more deliberately by introducing texts that require both fluent reading and higher-level comprehension strategies like summarizing, predicting, and making inferences.

Curriculum designers can use the rope as a checklist to ensure that instructional materials and assessments are comprehensive and aligned with how children actually learn to read.

Digital Tools and the Reading Rope

In today’s tech-rich classrooms, many educators use digital resources to supplement reading instruction. However, the key is to align those tools with the components of the rope.

For instance:

- Apps like Sound Town or Elkonin Boxes Online can target phonological awareness and decoding skills.

- Vocabulary.com or Freckle can help strengthen vocabulary and background knowledge.

- Newsela and ReadWorks offer leveled texts that support comprehension and encourage critical thinking across various genres and subjects.

Teachers should evaluate digital tools not by their popularity or aesthetic design but by how well they support one or more of the rope’s strands.

The Role of Assessment in the Rope Model

Assessment is critical to using the Reading Rope effectively. But it’s important to differentiate between summative assessments (which often evaluate overall reading proficiency) and diagnostic assessments (which identify specific strand-related weaknesses).

Examples of useful assessments include:

- Phonological awareness screeners (e.g., DIBELS or PAST)

- Decoding fluency measures (e.g., timed readings, nonsense word tests)

- Vocabulary knowledge tests (e.g., PPVT or teacher-created quizzes)

- Reading comprehension diagnostics (e.g., running records with comprehension checks)

Once gaps are identified, interventions should focus narrowly on those components. For example, a child struggling with syntax might benefit from sentence-combining exercises, while a child lacking background knowledge may need exposure to content-rich texts in science and social studies.

Supporting Multilingual Learners with the Rope

Scarborough’s Reading Rope is particularly helpful for supporting English Language Learners. Many ELL students demonstrate strong decoding skills but still struggle with comprehension due to limited vocabulary or unfamiliarity with idiomatic language.

For these students:

- Focused vocabulary instruction with visual supports is crucial.

- Exposure to diverse genres—like folk tales, poems, and informational texts—can build cultural and contextual understanding.

- Explicit teaching of language structures (e.g., compound sentences, prepositions, or modal verbs) can bridge gaps in grammar and syntax.

Additionally, background knowledge plays a critical role for ELLs. Teachers should activate and build this knowledge before reading by previewing topics and connecting them to students’ real-life experiences.

Bridging Home and School: Parent-Teacher Collaboration

One of the model’s hidden strengths is how well it supports meaningful conversations between educators and parents. When a child struggles, parents are often left wondering whether it’s a motivation issue, a cognitive challenge, or something else.

Using the Reading Rope as a guide, educators can clearly explain:

- Which specific strand needs support (e.g., decoding vs. comprehension)

- What kind of activities can help (e.g., phonics games or read-alouds)

- How progress will be measured over time

For instance, rather than telling a parent “your child needs to work on reading,” you might say: “Your child is doing well with recognizing words, but needs help understanding the meaning of more complex sentences. At home, you can help by reading together and asking questions like, ‘Why do you think that happened?’ or ‘What do you think the character is feeling?’”

This clarity helps demystify reading instruction and empowers parents to participate actively in their child’s growth.

Future Directions in Literacy Instruction

As literacy instruction continues to evolve, Scarborough’s Reading Rope remains a foundational model. It is not a program or curriculum but a research-based conceptual framework that supports flexible, responsive instruction.

Looking ahead:

- Teacher preparation programs are beginning to embed the rope model into coursework on reading science.

- Policy initiatives such as early literacy screening laws are aligned with rope-based diagnostics.

- Neuroscience and AI tools may soon provide even more precise assessments of how each strand is developing in individual learners.

By staying grounded in models like Scarborough’s Rope, educators can navigate these innovations while holding firm to what truly supports students—explicit, evidence-based instruction rooted in a deep understanding of how reading works.

Final Thoughts

So, what is Scarborough’s Reading Rope? It’s not just a diagram—it’s a roadmap for reading success. By breaking down the complex process of reading into two main strands and their subcomponents, educators and parents can better understand, assess, and teach reading skills.

With Scarborough’s rope model of reading, instruction becomes more precise, interventions more effective, and reading outcomes more successful.

By using this model:

- Teachers can implement evidence-based instruction.

- Parents can support their children’s growth.

- Students can become confident, skilled readers.

Whether you're introducing this model to your team, applying it to your classroom, or just discovering it for the first time, Scarborough’s Reading Rope stands as a foundational guide in the journey of reading development.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope gives us more than a metaphor—it gives us a lens through which to view the entire process of learning to read. By breaking down reading into its component parts, educators can make informed decisions, tailor instruction to meet students' needs, and communicate more effectively with families.

In a world where literacy opens doors to opportunity, equity, and lifelong learning, tools like Scarborough’s Reading Rope are more important than ever. Whether you're in a classroom, at home, or developing curriculum at the district level, understanding and applying this model can transform the way children learn to read.

Key Takeaways

- Scarborough’s Reading Rope breaks reading into two main strands: language comprehension and word recognition.

- Each strand is made up of several subskills that intertwine to form skilled reading.

- It is a vital framework aligned with the Science of Reading.

- Teachers can use it to assess, instruct, and intervene more effectively.

- Parents can better understand and support their children’s literacy development.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope makes one thing clear: reading is not simple, but with the right tools and frameworks, we can make it accessible to all. For your own PDF of the Scarborough Reading Rope, just click here!